- How diverse is the ACT’s biodiversity?

- Threatened species in the ACT

- Caring for land, caring for biodiversity

- Reduce invasive species, increase native biodiversity

What are the main natural environment and biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More findings from the 2019 ACT State of the Environment Report? See the infographic and video below to find out.

How diverse is the ACT’s biodiversity?

The ACT’s terrestrial and aquatic ecosystemsA collection of interacting living and non-living things. A More are home to many flora (plants) and fauna (animals) species. The urban environment also supports many species, either as a food source or a place to live. Records from Canberra Nature Map show that there have been 2,815 fauna species sighted in the ACT. This includes:

- 2,751 native species – 67 mammals, 298 birds, 14 snakes, 49 lizards, 37 frogs, 2 turtles, 28 fish, 188 spiders and 2068 insects.

- 64 introduced species – 17 mammals, 33 birds, 2 lizards, 1 frog and 11 fish.

The ACT also has many flora species, including:

- 2,088 indigenous species – 1,032 vascular plants, 263 fungi, 490 lichens, 3 hornworts, 77 liverworts, 195 mosses and 28 slime moulds.

- 592 introduced species, 53 of which were introduced from elsewhere in Australia.

There are also four plant species that are only native to the ACT. These are the Canberra Spider Orchid, Brindabella Midge Orchid, Ginninderra Peppercress and Tuggeranong Lignum.

Did you know?

Canberra and surrounds have the richest bird life of any Australian capital city. There are over 200 recorded species here. Birds come in many different sizes and colours, from the large emu, to the tiny Weebill.

Did you know?

Many highly mobile species such as birds also migrate through the ACT and may only be present for breeding, or in response to food and water availability. It is important to note that for these temporary residents, changes in their annual abundance and distributions in the ACT may result from external influences including changes to food availability, loss of habitat or increase in invasive species. Consequently, populations can increase or decrease regardless of the condition of the ACT environment. That is why it is important to protect native species and their habitats wherever they are found.

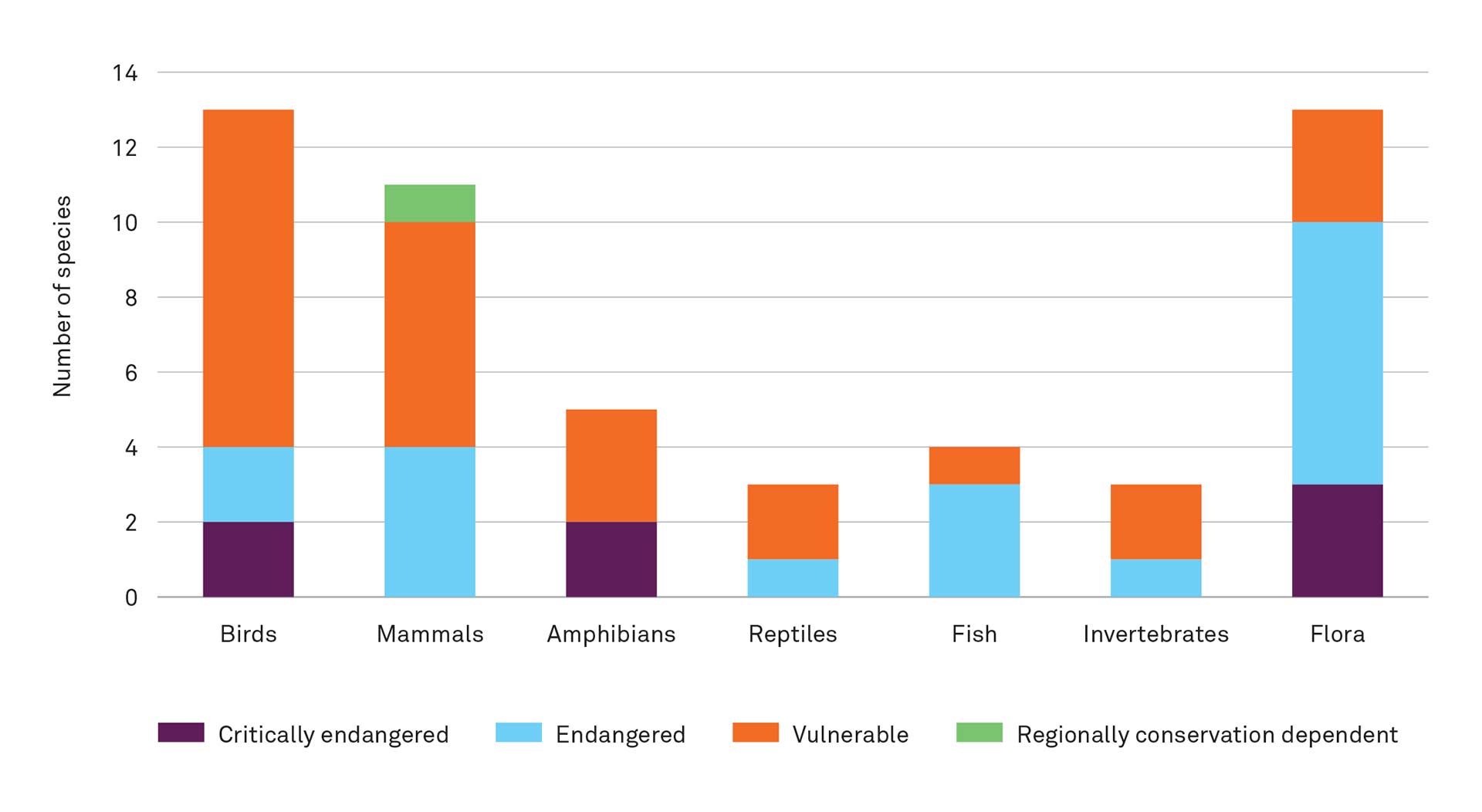

Threatened species in the ACT

It is not possible to accurately measure the distribution and abundance of all species in the ACT. This is because not all species occurring in the ACT are known, let alone counted, and not all areas of the ACT can be surveyed and monitored. That means assessment of biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More is mainly focused on threatened species. Threatened species are those that are at risk of becoming endangered due to losses or changes to their habitat or a reduction in their population numbers. A species can be threatened over a large area (e.g. threatened in Australia), or in a specific area (e.g. threatened in the ACT).

A threatened species is given a conservation status based on the level of threat to its survival. A species can be classed as:

- Critically endangered: a species is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future.

- Endangered: a species is facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future.

- Vulnerable: a species is facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium-term future.

- Regionally conservation dependent: a species dependent on management.

Many species need our help. There are 52 fauna and flora species listed as threatened in the ACT. This includes:

- 7 critically endangered species

- 18 endangered species

- 26 vulnerable species

- 1 species (the Eastern Bettong) regionally conservation dependent

- 3 endangered environments: the Natural Temperate Grassland, Yellow Box/ Red Gum Grassy Woodland, and High CountryA bounded geographical area, distinct from one another. Coun More Bogs and Associated Fens.

The grassland earless dragon is endangered. Photo: Mark Jekabsons

The corroboree frog is critically endangered. Photo: Murray Evans

Murray river crayfish is vulnerable. Photo: Mark Jekabsons

The superb parrot is vulnerable. Photo: Ryan Colley

The regent honeyeater is critically endangered. Photo: Ryan Colley

The swift parrot is critically endangered. Photo: Ryan Colley

A full list of the ACT’s threatened species and the main impacts on them can be found HERE

Changes in conservation status show that of our native species are under more pressure from a range of impacts such as climate change, invasive species, fire and habitat loss. Between 2015 and 2019, 17 additional species were listed as threatened in the ACT.

Did you know?

The most common threats to biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More in the ACT are:

Caring for land, caring for biodiversity

Conservation areas provide enough land for species to move and breed with less human interference. These areas include large areas of native vegetation within the ACT. Native vegetation is important for biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More because it provides habitat and protects soil from erosion.

Urbanisation and agriculture have resulted in the need to clear vegetation from parts of the ACT. To compensate for land development, environmental offsetsAn area of land preserved and improved to compensate for the More aim to ensure that when land is developed, other similar land is preserved elsewhere. It is important that the offset land is similar to the developed land in terms of size, species and level of biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More.

To maintain biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More, more than half of the ACT is dedicated to conservation habitat – in 2019 it was 60 per cent (141,000 hectares) and continues to increase mainly though environmental offsetsAn area of land preserved and improved to compensate for the More which currently protect 1,865 hectares of ecosystemsA collection of interacting living and non-living things. A More in the ACT.

Protecting all types of ecosystems

There are many different types of vegetation ecosystemsA collection of interacting living and non-living things. A More in the ACT and it is important to protect adequate areas of all them, and the biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More they support. The least protected vegetation communities in the ACT are woodland, grassland and open forest communities. Only 30 per cent of these ecosystemsA collection of interacting living and non-living things. A More are protected in conservation areas.

Vegetation loss and restoration

Vegetation loss is a problem because animals may not be able to move through and between different areas. This is why cities, towns and farms can pose a threat to biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More as species cannot pass these barriers to migrate and breed.

Revegetating cleared areas is an important way to support biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More. It not only restores habitat, but creates corridors for species to move between areas of habitat. Between 2015 and 2019, there were 100,000 native plants and 200 kilograms of native seeds planted on the ACT’s public land. Between 2015 and 2018, 1,500 hectares of private land were also revegetated. While growing new trees is important in areas that have been cleared, it is also important to save old trees because these provide habitat such as hollows where birds and possums can live. Large, old trees can be damaged by disease, insects and drought. Around Canberra, Blakley’s red gum is a species that is suffering due to the pressures of climate change: older trees are dying and the dry conditions are too tough for younger trees to establish. If this continues, these trees will not be able to survive and the animals that call them home will struggle.

Reduce invasive species, increase native biodiversity

Even in conservation areas, invasive species can harm native biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More. Supporting biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More means removing invasive ones. The ACT’s native species continue to be significantly affected by invasive animals such as feral pigs, deer, foxes, rabbits, horses and wild dogs, as well as a range of invasive plants. These can reduce biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More by feeding on native animals, competing with them for food and habitat, by spreading disease and parasites, and by displacing the native flora species that provide habitat and food.

Rabbits are the most damaging invasive species in the ACT. They dig up native vegetation and cause erosion, making it difficult for native plants to grow. Lack of native vegetation reduces the habitat and food available for native animals and insects, and lets weeds grow. Rabbits can very quickly turn a healthy environment full of many different types of native plants and animals into a paddock containing just one type of weed. Rabbits breed quickly, so their numbers can rise rapidly. As rabbits are a food source for foxes, more rabbits lead to more foxes, which then prey on small native species. Foxes have even caused local extinctions, such as those of the Bettong, small, nocturnal marsupials.

Horses, deer, cattle and other hooved farm animals can damage the environment when free to roam in native bush such as the high countryA bounded geographical area, distinct from one another. Coun More. Unlike any native Australian animal, these animals have hard hoofs that erode the ground, removing grasses and disrupting soil. Eroded soil can then wash into local waterways. Hard hoofs can also destroy fragile alpine bogs, which are important for regulating water flow from alpine regions as they slowly release snow melt, feeding rivers and supporting ecosystemsA collection of interacting living and non-living things. A More downstream.

Feral pigs, wild dogs and Indian Myna birds are also problematic invasive species. The ACT has recognised this and there are programs, such as baiting and trapping, to control their numbers.

Native animals can also threaten biodiversityThe variety of all life and living processes in the environm More. When in high numbers, kangaroos are considered pests. Too many kangaroos continually eating grasses, means that the plants don’t have a chance to recover. This leads to erosion, making it even harder for native plants to grow. Weeds, often well suited to harsh growing conditions, can then take over, damaging the environment irreparably. Such changes have flow-on effects, as native species lose their habitat or food source, so die out or must relocate, possibly then disrupting an ecosystemA collection of interacting living and non-living things. A More elsewhere.

Did you know?

Cats, despite hunting many native birds, reptiles and small mammals, are not managed by any programs other than domestic cat containment laws. These laws state that if you live in an area where conservation is under threat from cats, you must keep your cat indoors, or in a cage outdoors. Find out if you live in a cat containment area HERE